Written By: Finn O’Connor

For some, the holiday season is an opportunity to connect with family and friends who we often do not get to see more than once a year. For others, it is a chance to remind ourselves why we only see our family once a year as we get the opportunity to revisit the same old disagreements from the last holidays and sit uncomfortably around the dinner table for five hours.

International relations can seem a lot like the latter at times, especially between democratic countries who are often forced to interact in global forums despite their personal misgivings with one another. Most of the time, allies bite their tongue and get to business without dredging up the ugly stuff. However, from time to time, two family members get into a row across the table while the other patrons awkwardly watch from the sidelines.

Despite being on other sides of the world, the two countries have a surprising amount in common. A parliamentary system inherited from the late British Empire, a vast territory covered in a harsh climate that sometimes borders on unhospitable, and an array of regional cultures that often chafe against the idea of a national identity. However, within these similarities are fundamental differences. Canada is temperate and can be bitingly cold, while India is tropical and brutally hot. Canada’s regional identities stem from its population’s colonial homelands, whereas many of India’s cultures predate the European nations themselves. And, while Canada’s democracy persists in a recognizable form, the Indian government has increasingly toyed with authoritarianism and nationalism.

Notwithstanding its structure of a representative democracy, the Indian government’s record on human rights has declined since its current Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, took power nine years ago (1). Despite this, India’s democratic allies pushed ahead, with the UK working to a complete an FTA with New Delhi that did not include any clear human rights protections (2).

The internal tensions are now out in the open as Canadian Prime Minister Trudeau went public with the allegation that the Indian government sanctioned an assassination on Canadian soil. The ensuing row between the two allies has prompted concern that the disagreement might escalate from rhetoric to a minor trade war as either side attempts to exert pressure on the other. The question is, then, who holds the upper hand if the gloves come off.

Trade wars are different from conventional wars, where militaries measure their relative strength to achieve their respective objectives, and more like the grinding wars of attrition we are increasingly seeing in the 21st Century. The name of the game comes down, in essence, to hurt the other’s economy while avoiding as much damage to your own as possible. This can be particularly difficult in an economic sense as many trade relationships are two-way streets in which both sides benefit from arrangements, so cutting ties in certain sectors can mean hurting your own economy. Thus, the best ways to exert power on another country is to target sectors where they are more reliant on you than you are on them, or to strengthen relationships with other countries to mitigate the damage. India’s first advantage is in this regard.

Strategic Considerations

First, India is a key component in Western Democracies’ Asia strategy. As the largest democracy in Central Asia, Western planners increasingly prioritized maintaining an economic relationship with the country as other major players, such as Russia and China, become more isolated from the global economy. It seemed, for a time, as though India’s large population (on track to surpass China’s by 2050) and growing economy positioned it as a democratic alternative to Beijing as a global manufacturing hub. But even regardless of its democratic backsliding New Delhi remains a key factor in the West’s strategic goals in the Indo-China region, with the US recently making efforts to deepen defence ties between the two nations (3).

It is within this strategic context that the dispute between India and Canada unfolds. In a trade war, one’s power lies in the strength of its allies and given the importance of the US-India relationship to American foreign policy, it appears as though the two countries stand alone, which limits the use of tools such as embargoes. Thus, the competition will come down to the bilateral relationship between the two countries.

Inter-Country Trade

Since 2010 Canada and India have engaged in negotiations to form a Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA) that would, in effect, remove tariffs on most bilateral trade. At the time, the Government of Canada designated India a “high-priority trading partner” (4). By the end of September 2022, the two wrapped up the fourth round of talks on an Early Progress Trade Agreement (EPTA). At the time, bilateral trade seemed to be on its way to reaching its full potential. It is estimated that, if Canada had traded at the same level, it did with other partners, that merchandise exports to India could have been 242 per cent higher between 2017 and 2019 (5). The result is that Canada benefitted only marginally from India’s rapidly growing economy. One factor in the low exports is India’s protectionist tendencies towards its domestic industries. However, with agreements with the UAE and Australia in works, Canada’s CEPA stood to realize the potential of trade ties with India (6). Following the allegations, Ottawa suspended CEPA talks indefinitely.

Aside from what might have been, we remain with what is. Over ten years, trade between India and Canada grew from $3.87 billion to $10.18 billion, driven by exports in energy products and the import of consumer goods.

Despite being a major refined petroleum exporter, the vast majority of Indian imports to Canada are consumer goods (7)

While it is unlikely that trade will completely stall between India and Canada, it is possible that either country might throttle certain sectors to exert political pressure.

Other Avenues

India also retains a number of softer channels of economic influence such as the export of international students. According to StatsCan’s Tuition and Living Accommodation Costs survey, international students paid 43.5 per cent of all tuition fees in 2020 (8). Indian citizens make up the largest portion of Canada’s international students at 28 per cent in 2022 (9). This leaves Canadian universities vulnerable to being cut off from a major source of income. While an official stance may seem unlikely, there is precedent. Following a series of attacks targeting Indians in Australia in 2009, New Delhi discouraged its citizens from enrolling there (10). In 2020, at the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, international student enrollment dropped by 17 per cent from the previous year which, in turn, contributed to a loss of $7.1 billion from Canada’s GDP, or equal to 64,300 full-time jobs (11).

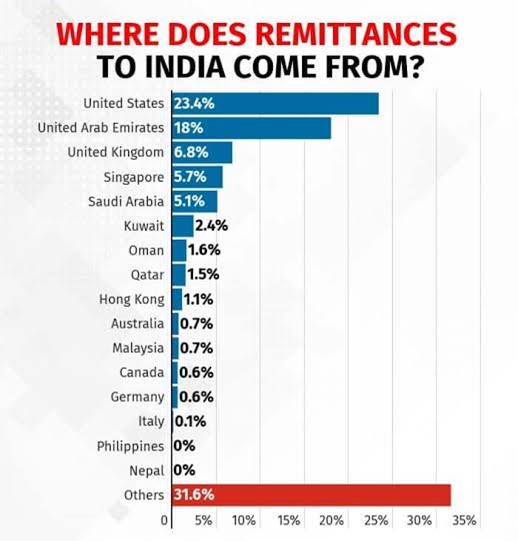

Canada’s one saving grace is that India stymying the flow of immigrants might likewise decrease the amount of money sent from migrants back to their families. As of 2022, India led the world in received remittances (12). The cashflows are not only critical to supporting India’s Balance of Payments, keeping current receipts afloat during the Indian BoP crisis following the 1990 Gulf War (13). However, Canada is only the ninth largest source of remittances to India, providing $3.8 million in 2021 (14). Even here it is eclipsed by the massive remittance inflows of Saudi Arabia, Qatar and even the US.

While Canada does make this list, its contribution to remittances remains paltry compared to the larger players (15).

It seems, as of now, that India holds the upper hand in trade disputes. New Delhi can take advantage of its strategic position to mitigate the loss of trade with Canada. The UK and US appear to prioritize the importance of a strong Indo-Pacific ally over punishing transgressions between alliance members. At the same time, Canada and its allies have a significant interest in India’s green energy transition. Even though a pause in CleanTech investment might hurt the Indian economy, the transnational nature of climate change means Canada ultimately stands to lose if the third-largest producer of carbon emissions fails to meet its net-zero targets.

However, there is one factor which might skew the relationship in Canada’s favor. Recent reports suggest that American intelligence provided some of the evidence of India’s involvement in Nijjar’s killing (16). US Secretary of State Blinken is encouraging India to cooperate with the investigation, suggesting that they might intervene if the dispute escalates. US intervention might allow Canada to exercise more power in retaliation against Indian sanctions. Unlike Canada, America is India’s largest trading partner with bilateral trade reaching $157 billion in 2021 (17). The US is also the second largest source of remittances to India with a nearly 18 per cent share (18).

However, it is still a reluctant player in the dispute, still hesitant to alienate India as a key strategic partner. Most of it comes down to the fact that an alliance with Canada is a given, whereas one with India is still in its early stages. Recent US foreign policy also gives cause for concern. It has strengthened ties with Saudi Arabia and neglected to intervene in Israel’s recent erosion of democratic norms under Netanyahu’s administration, all with eye towards stemming Chinese influence in the Middle East (19). It seems unlikely that the US will choose a normative imperative over a strategic one, particularly in a dispute involving a country right in China’s backyard.

So, for now, it appears as though Canada stands alone, and on the back foot. Regardless of how justified its complaints might be, it simply cannot compete with the Free World’s golden child.

Works Cited

- Salil Tripathi, “India’s Worsening Democracy Makes It an Unreliable Ally,” Time, June 20, 2023, https://time.com/6288505/indias-worsening-democracy-makes-it-an-unreliable-ally/

- Human Rights Watch, “India: Events of 2022,” in World Report 2023, 2023, https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2023/country-chapters/india.

- Joseph Clark, “U.S.-India Relationship Critical to Free, Open Indo-Pacific,” U.S. Department of Defense, September 19, 2023, https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/3531303/us-india-relationship-critical-to-free-open-indo-pacific/https%3A%2F%2Fwww.defense.gov%2FNews%2FNews-Stories%2FArticle%2FArticle%2F3531303%2Fus-india-relationship-critical-to-free-open-indo-pacific%2F.

- Global Affairs Canada, “Canada-India Free Trade Agreement Negotiations,” GAC, March 2021, https://www.international.gc.ca/trade-commerce/trade-agreements-accords-commerciaux/agr-acc/india-inde/fta-ale/background-contexte.aspx?lang=eng.

- Dan Ciuriak et al., “Assessing Export Opportunities for Canada in India,” SSRN Scholarly Paper (Rochester, NY, January 28, 2022), 12, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4021609.

- Pia Silvia Rozario, “A Free Trade Agreement for Canada and India: Is the Time Finally Right?,” Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada, accessed October 17, 2023, https://www.asiapacific.ca/publication/free-trade-agreement-canada-and-india-time-finally-right.

- Consulate General of India, “India Canada Trade,” Consulate General of India, accessed October 17, 2023, https://www.cgitoronto.gov.in/page/india-canada-trade/.

- Erudera News, “Tuition Raises: Canadian Universities Benefiting More from International Students Annually,” Erudera, August 17, 2023, https://erudera.com/news/tuition-raises-canadian-universities-benefiting-more-from-international-students-annually/.

- Shruti Srivastava, “India’s Clash With Canada Threatens to Hurt Trade, Investment – BNN Bloomberg,” BNN, September 26, 2023, https://www.bnnbloomberg.ca/india-s-clash-with-canada-threatens-to-hurt-trade-investment-1.1976822.

- “Tensions with India Raise Concerns Fewer International Students Will Choose to Study in Canada,” The Globe and Mail, September 20, 2023, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-tensions-with-india-raise-concerns-fewer-international-students-will/.

- Global Affairs Canada, “The Economic Impact of COVID-19 on Canada’s International Education Sector in 2020” (Global Affairs Canada, September 1, 2021), https://www.international.gc.ca/education/report-rapport/covid19-impact/index.aspx?lang=eng.

- Jijin, Alok Kumar Mishra, and M. Nithin, “Macroeconomic Determinants of Remittances to India,” Economic Change and Restructuring 55, no. 2 (2022): 1229–48, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10644-021-09347-3.

- Prepared Michael Debabrata and Muneesh Kapur, “India’s Worker Remittances: A Users’ Lament About Balance of Payments Compilation,” Department of Economic Analysis and Policy Reserve Bank of India, December 2005

- “Canada among Top Choices for Indians but Economic Bond Remains Weak,” The Economic Times, September 21, 2023, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/nri/migrate/canada-among-top-choices-for-indians-but-economic-bond-remains-weak/articleshow/103791550.cms?from=mdr.

- Reserve Bank of India, “Headwinds of COVID-19 and India’s Inward Remittances,” Rbi.Org, July 16, 2022.

- Julian E. Barnes and Ian Austen, “U.S. Provided Canada With Intelligence on Killing of Sikh Leader,” The New York Times, September 23, 2023, sec. U.S., https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/23/us/politics/canada-sikh-leader-killing-intelligence.html.

- “U.S. Relations With India,” United States Department of State (blog), accessed October 6, 2023, https://www.state.gov/u-s-relations-with-india/.

- The Economic Times, “Canada among Top Choices for Indians but Economic Bond Remains Weak.”

- Howard W. French, “Washington Is Losing Credibility Over the Canada-India Spat,” Foreign Policy (blog), September 27, 2023, https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/09/27/canada-india-sikh-separatist-assassination-biden-us-response-modi-democracy/.